Coming out of the 37th JP Morgan Health Conference in San Francisco and the 51st Edition of the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas last week, three themes were prominent in both:

-

Healthcare is ripe for disruption. It’s too costly, unnecessarily complicated and structurally flawed.

-

Engaging consumers and leveraging technology are keys to its disruption.

-

Primary care, constructed right, is the bridge from the status quo to a system of health that’s efficient and effective.

The question is who will build the bridge?

THE REALITIES ABOUT PRIMARY CARE

Healthcare is expensive. Research indicates as much as 30% of what’s spent is wasted. Unnecessary tests and procedures, redundant administrative paperwork and the high prices we pay for drugs and specialty care are the culprits.

By contrast, we under spend for primary care. It’s 7.7% of total healthcare spending but if funded appropriately and orchestrated right, it’s key to lowering health costs long-term by reducing demand for expensive services and managing the population’s health.

Traditional approaches to primary care have faltered: providers of primary care services are odd man out in the politics and economics of U.S. healthcare. Providers of primary and preventive health services to uninsured and under insured populations operate in a parallel universe. For 28 million, there are 11,000 community health centers and hospital emergency rooms to serve their primary care needs. For the rest, it’s a cadre of services offered by retail clinics, urgent care clinics, physicians and others accessible through private insurance or direct out of pocket payments.

In both the public health and private settings, social determinants of health (SDOH) are a centerpiece in their care models. Food insecurity, loneliness, anxiety, housing, income disparity and other ‘risk factors’ were considered by clinicians long before payers like Medicare adjusted their payments based on the social circumstances of their patients. Primary care has been and will continue to be the front-line for SDOH.

So, given the increased prevalence of chronic diseases in our population and its associated costs, the business case for a fresh approach to primary care is compelling. It is based on four assumptions:

1. Increased access to continuous and effective primary care services reduces health costs by reducing utilization of specialists and hospitals.

Primary care represents 5.8-to 7.7% of total health spending in the U.S. But in states like Rhode Island where increased PC outflows went to 9% from 6% over a four-year period (2008 to 2012), overall spending reduced by 14%.Done right, primary care is an investment that reduces costs and improves population health status.

2. The soaring demand for primary care cannot be met by traditional models of delivery.

The complexity of patient care seen in primary care settings is increasing demand. The industry now acknowledges that social determinants of health and other factors may impact up to 90% of outcomes. Technology-enabled care coordination, modernized clinical models that integrate physical, behavioral and social factors and consumer engagement are required. Thus, access to primary care is no longer defined by office visits or the numbers of DO’s or MD’s per 100,000 in a community. It’s physical locations and virtual care. It’s services provided by physicians, mid-level practitioners, alternative health providers and individuals for themselves and their families. It’s about lifestyle, not just values from lab tests and physical exams. And it’s about the food we eat, air we breathe and social settings where we live, not just prescriptions and tests. Accommodating burgeoning demand for primary care requires sophisticated capabilities delivered at scale by organized teams of providers. It requires capital, strong management and contracts that reward better outcomes and lower costs.

3. The public is welcoming of advanced practice nurses, retail clinics, alternative health providers and pharmacists as providers of primary care services.

It cuts across all generational cohorts and is evident in utilization shift. Per government data, office visits to primary care physicians (PCPs) declined 18% from 2012 to 2016 for adults under 65 years old with employer-sponsored health insurance, while office visits to nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) increased 129%. Comparing 2012 to 2016, there were 273 fewer office visits/1,000 insured individuals to primary care physicians over that span, while visits to nurse practitioners and physician assistants rose from 88/1,000 insured members to 201. The public recognizes the need for primary care but thinks it’s more than scheduled visits to doctor’s offices.

4. The economics of primary care are not conducive to capital investments necessary to manage health and coordinate care.

To rationalize the capital required to fund modern primary care, business partners are needed. Compared to specialists, income associated with primary care is lower, costs associated with these practices is higher and opportunities to generate additional income from in-office diagnostics or outside ownership interests fewer. To illustrate: in 2016, the average cost per visit to a primary care physician was $106 compared to $103 for an office visit to a NP or PA. Per Sullivan Cotter, the average starting salary for family physicians was $266,552 last year– up 1% from 2016-2017 and $278,946 for internists– up 1.2% from 2016-2017. By comparison, orthopedists earned $632,066 (+1.76%), invasive cardiologists $625,180 (+1.16%), general surgeons $431,852 (-2.13%) and so on. Thus, returns on investment in primary care are dependent on reduced use of hospitals and specialty services. That requires infrastructure, systems, management, analytics and technologies most primary care practices have not been able to afford. That’s why only 28% of PCPs own and operate their own practices (AAFP). It’s a tough business to run.

THE THREE BUSINESS MODELS FOR PRIMARY CARE

Based on these assumptions and growing discontent about healthcare affordability, the industry is paying more attention to primary care. Two models are prevalent in most communities:

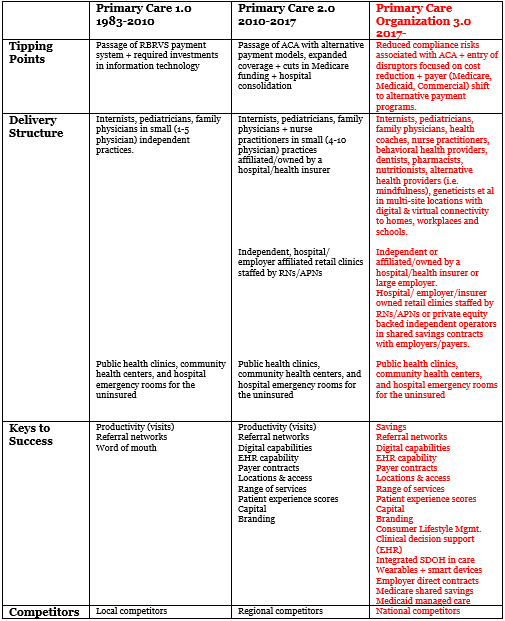

Primary Care 1.0 centers on the capacity of physician(s) to manage 30-35 visits daily and maintain a strong word of mouth reputation among patients and colleagues. It’s still the dominant model in rural communities and popular among late career clinicians who prefer complete autonomy. Marcus Welby MD, ABC’s iconic prime-time clinician (1969-1976) is the prototype.

Primary 2.0 reflects a response to prospective payments, managed care, hospital consolidation and federal requirements for electronic medical records. It is essentially a bigger version of 1.0 with some added capabilities. Efforts by the American College of Physicians, Primary Care Development Corporation, American Academy of Family Physicians, Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative, American Association of Nurse Practitioners, American Board of Family Medicine and others have added advocacy clout to Primary Care 2.0 efforts. It’s a prominent model in most communities and a focus for hospitals seeking to control referrals to their specialists and for insurers seeking to control use of efficient providers in their networks.

These models are largely dependent on the productivity of the physicians and word of mouth among patients about their effectiveness.

Primary care 3.0 is a quantum leap forward. It’s the bridge from the unsustainable status quo to tomorrow’s system of health:

THE BRIDGE BUILDERS: BUSINESS PARTNERS WHO WANT TO BE AT THE TABLE WITH CLINICIANS

To achieve success in Primary Care 3.0, capital, management and access to patients (consumers) via managed care contracts are requisites. Infrastructure and information systems are key. Team based care coordination is essential. Data-driven decision-making is imperative. And the scale and scope of services offered to managed care, employers and directly to individuals is dramatically bigger.

Some primary care practices are progressing toward Primary Care 3.0 using their own resources and debt to make investments and maintain their independence. Most will engage with business partners who bring capital, operating expertise, purchasing power and management experience. In recent months, four types of partnerships have emerged: each has its pros and cons:

1. Hospitals/Health Systems:

Pro’s: Hospitals bring community relationships and trust; a clinical culture along with technologies and facilities that support patient care needs.

Cons: A hospital’s cost structure and overhead are high; its cultural dependence on admissions and outpatient visits to drive revenue growth creates headwinds and its regulatory constraints are complex.

Considerations: Physician compensation in hospital-owned groups is lower than private practitioners and hospital operating losses for owned groups are significant. Nonetheless, their investments in Primary Care 3.0 will be made to protect referrals to their services and position the organization for alternative payment programs like Medicare Shared Savings (ACOs) and others. Key Fact: hospital ownership of practices increased 63% in the last 5 years. In most cases, physician compensation is primarily productivity based unless operating under capitated contracts with payers.

2. Insurers

Pro’s: Insurers bring data about utilization, risks, outcomes and costs; employer relationships and capabilities in care coordination. Their strength is cost-management, relationships with employers and and operating experience in Medicaid managed care and Medicare Advantage.

Cons: Public trust in health insurers is low and their cultural bias against physicians and hospitals creates tension. Insurers value standardization and discount clinical judgment and appropriate variability in care.

Considerations: Insurers believe directing care to narrow networks of efficient and effective providers is key to their success. They look to PC 3.0 to direct care to their preferred providers short term and to reduce demand for hospitals, specialists and expensive drugs long-term.

3. Private Investors:

Pro’s: Private capital is return-focused. Monetizing savings for reduced use of hospitals, specialists and expensive drugs are keys to the profitability in Primary Care 3.0. Given the level of unnecessary care that’s provided and the wide variability in hospital costs, the upside is significant for the investors and clinicians. In most cases, private investors own the majority interest in the enterprise while encouraging physicians as minority shareholders.

Con: Private investors seek an annual return of 20% or more and most wish to liquidate their position in 5-7 years. That puts enormous pressure on managers and often creates tension with clinicians. Private investors seek an exit strategy from day one of the relationship. Therefore, clinicians must be prepared for ownership changes.

Considerations: Return on investments in primary care 3.0 by private investors are dependent on physician leadership, aggressive care coordination to reduce unnecessary utilization of hospitals and prescription drugs and contracts with payers that reward these efforts. Medicare Advantage is a classic opportunity: it’s popular among seniors, profitable to insurers and growing.

4. Retail Health:

Pro’s: The likes of Apple, CVS, Amazon and other retailers bring expertise in marketing to consumers based on sophisticated analytics, brand identity, access to distribution systems to support access, digital connectivity within their supply chains and with customers, experience with alternative and over-the-counter therapies and scale. The retail giants that have targeted healthcare appreciate the integration of health and social services, healthy lifestyles and mass customization in their delivery.

Cons: Retailers lack a clinical culture wherein physicians may feel comfortable. Retailers think about consumers and customers; physicians think about patients.

Considerations: CVS’ CEO told investors at JPM that its retail clinics are “the front door to the health system” and promised to expand them. Apple CEO told CNBC: “If you zoom out into the future, and you look back, and you ask the question, ‘What was Apple’s greatest contribution to mankind?’ It will be about health. … We are democratizing it. We are taking what has been with the institutions and empowering the individual to manage their health.” For many retailers, healthcare represents a huge opportunity for growth by creating a strong value proposition for consumers.

Each of these four has a different architectural rendering of the bridges they wish to build to Primary care 3.0. All are betting that the costs of the current system are not sustainable, its outcomes modest and the public’s appetite for something better palpable. They’re betting most will cross the bridge.

Paul

P.S. Reminder: Friday, January 18, organizations wishing to participate in the Medicare Shared Savings Program (ACO) starting July 1, 2019 and continuing for 5 years must submit a Notice of Intent to CMS https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/for-acos/application-types-and-timeline.html

Resources:

-

Primary Care 2.0: A Vision for a Transformative Solution (March, 2014)

-

Primary Care 2.0: The Front Line in Health Reform (October 2015)

-

Myth: There’s a Physician Shortage in Health Care (March 2018) https://www.paulkeckley.com/the-keckley-report/2018/3/12/myth-theres-a-physician-shortage-in-the-us

-

Primary Care 3.0: The Front Door to Health System Transformation (September 2018)

Nice blog yoou have